Congress Poland

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

|

| Polish statehood |

| Poland |

| Kingdom of the Piasts

Kingdom of the Jagiellons Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Partitions of Poland Kingdom of Galicia Duchy of Warsaw Kingdom of Poland (Congress Poland) Grand Duchy of Posen Grand Duchy of Cracow Second Polish Republic Polish Underground State People's Republic of Poland Third Polish Republic |

| Poland portal |

The Kingdom of Poland (Polish: Królestwo Polskie [kruˈlɛstfɔ ˈpɔlskʲɛ], Russian: Царство Польское, Tsarstvo Polskoye, Russian pronunciation: [ˈtsarstʋə ˈpolʲskəje], translation: Tsardom of Poland), informally known as Congress Poland Polish: Królestwo Kongresowe [kruˈlɛstfɔ kɔnɡrɛˈsɔvɛ] or Russian Poland) was a constitutional personal union of the Russian Empire created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, replaced by the Central Powers in 1915 with the Kingdom of Poland.[a] Though officially the Kingdom of Poland was to begin its statehood with considerable official political autonomy, the kings generally disregarded any restrictions on their power and severely curtailed autonomous powers following uprisings in 1830-31 and 1863 turning it first into a namestnik of the Russian Empire and later dividing it into guberniya (provinces).[1][2] Thus from the start the Polish autonomy remained nothing more than fiction.[3]

The territory of the Polish Kingdom roughly corresponds to the Lublin, Łódź, Masovia and Świętokrzyskie voivodeships of Poland.

Contents |

Naming

Although the official name of the state was the Kingdom of Poland, in order to distinguish it from other Kingdoms of Poland, it was sometimes referred to as Congress Poland.

History

The Kingdom of Poland was created out of the Duchy of Warsaw at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, when European states reorganized Europe following the Napoleonic wars. The creation of the Kingdom created a partition of Polish lands in which the state was divided and ruled between Russia, Austria and Prussia.[4] The Congress was important enough in the creation of the state to cause the new country to be named for it.[5][6] The Kingdom lost its status as a sovereign state in 1831 and the administrative divisions were reorganized. It was sufficiently distinct that its name remained in official Russian use, although in the later years of Russian rule it was replaced [7] with the Privislinsky Krai (Russian: Привислинский Край). Following the defeat of the November Uprising its separate institutions and administrative arrangements were abolished as part of increased Russification to be more closely integrated with the Russian Empire. However, even after this formalized annexation, the territory retained some degree of distinctiveness and continued to be referred to informally as Congress Poland until the Russian rule there ended as a result of the advance by the armies of the Central Powers in 1915 during World War I.

Originally, the kingdom had an area of roughly 128,500 km2 and a population of approximately 3.3 million. The new state would be one of the smallest Polish states ever, smaller than the preceding Duchy of Warsaw and much smaller than the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which had a population of 10 million and an area of 1 million km2.[6] Its population reached 6.1 million by 1870 and 10 million by 1900. Most of the ethnic Poles in the Russian Empire lived in the Congress Kingdom, although some areas outside it also contained Polish majority.

The Kingdom of Poland largely re-emerged as a result of the efforts of Adam Jerzy Czartoryski,[8] a Pole who aimed to resurrect the Polish state in alliance with Russia. The Kingdom of Poland was one of the few contemporary constitutional monarchies in Europe, with the Emperor of Russia serving as the Polish King. His title as chief of Poland in Russian, was Tsar, similar to usage in the fully integrated states within the Empire (Georgia, Kazan, Siberia).

Initial independence

Theoretically the Polish Kingdom in its 1815 form was a semi-autonomous state in personal union with Russia through the rule of the Russian emperor. The state possessed the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland, one of the most liberal in 19th century Europe,[8] a Sejm (parliament) responsible to the King capable of voting laws, an independent army, currency, budget, penal code and a customs boundary separating it from the rest of Russian lands. Poland also had democratic traditions (Golden Liberty) and the Polish nobility deeply valued personal freedom. In reality, the kings had absolute power and the formal title of Autocrat, and wanted no restrictions on their rule. All opposition to the emperor was persecuted and the law was disregarded at will by Russian officials.[9] though the absolute rule demanded by Russia was difficult to establish due Poland's liberal traditions and institutions. The independence of the Kingdom lasted only 15 years; initially Alexander I used a title of the King of Poland and was obligated to observe resolutions of the constitution. However, in time the situation changed and he granted the viceroy, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, almost dictatorial powers.[5] Very soon after Congress of Vienna resolutions were signed, Russia ceased to respect them. In 1819 Alexander I abolished freedom of the press and introduced preventory censorship. Resistance to Russian control began in 1820s.[3] Russian secret police commanded by Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev started persecution of Polish secret organizations and in 1821 the King ordered the abolition of Freemasonry which represented patriotic traditions of Poland.[3] Beginning in 1825 the sessions of the Sejm were held in secret.

Uprisings and loss of autonomy

Alexander I's successor, Nicholas I was crowned King of Poland on 24 May 1829 in Warsaw, but he declined to swear to abide by the Constitution and continued to limit the independence of the Polish Kingdom. Nicholas rule was representing the idea of Official Nationality, that is Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality. In relation to Poles those ideas meant the goal of assimilation, that is turning them into loyal Orthodox Russians.[3] The principle of Orthodoxy was the result of special role it played in Russian Empire, as the Church was in fact becoming a department of state,[3] and other religions discriminated, for instance papal bulls in the Kingdom of Poland could not be read without agreement from Russian government. The rule of Nicholas also meant end of political traditions in Poland, it ended the existence of democratic institutions, introduced centralized administration that was not elected but appointed, and it tried to change relations between state and individual. All of this led to discontent and resistance among Polish population.[3] In January 1831 the Sejm deposed the Nicholas I as King of Poland in response to his repeated curtailment of its constitutional rights. Nicholas reacted by sending Russian troops into Poland and the November Uprising broke out.[10]

Following an 11-month military campaign the Kingdom of Poland lost its semi-independence and was subsequently integrated much more closely to the Russian Empire. This was formalized through the issuing of the Organic Statute of the Kingdom of Poland by the Emperor in 1832, which abolished the constitution, army and legislative assembly. In the next 30 years a series of measures bound Congress Poland ever more closely to Russia. In 1863 the January Uprising broke out, but was crushed by 1865. As a direct result any remaining separate status of the Kingdom was removed and the political entity was directly incorporated into the Russian Empire. The formerly unofficial name of Privislinsky Krai (Russian: Привислинский Край) replaced Kingdom of Poland as the area's official name and the area became a namestnichestvo under the control of a namestnik until 1875, when it became a Guberniya.

Government

The government of the Congress of Poland was outlined in the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815. The Emperor of Russia was the official head of state, considered the King of Poland, with the local government headed by the Namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland, Council of State and Administrative Council, in addition to the Sejm.

In theory Congress Poland possessed one of the most liberal governments of the time in Europe,[8] but in practice the area was a puppet state of the Russian Empire. The liberal provisions of the constitution, and the scope of the autonomy were often disregarded by the Russian officials.[6][8][9]

Executive Leadership

The office of Namestnik was introduced in Poland by the Constitution of Congress Poland (1815), in its Article 3 (On the Namestnik and Council of State). The namestnik was chosen by the King from among the noble citizens of the Russian Empire or the Kingdom of Poland, excluding naturalized citizens. The namstnik supervised the entire public administration and, in the monarch's absence, chaired the Council of State, as well as the Administrative Council. He could veto the councils' decisions; other than that, his decisions had to be countersigned by the appropriate government minister. The namestnik exercised broad powers and could nominate candidates for most senior government posts (ministers, senators, judges of the High Tribunal, councilors of state, referendaries, as well as bishops and archbishops).

The namestnik had no competence in the realms of finances and foreign policy; his military competence varied.[b] In the event that the namestnik were unable to exercise his office due to resignation or death, this function would be temporarily carried out by the president of the Council of State.

The office of namestnik was never officially abolished; however, after the January 1863 Uprising it disappeared. The last namestnik was Friedrich Wilhelm Rembert von Berg, who served from 1863 to his death in 1874. No namiestnik was named to replace him;[11] however, the role of namestnik—viceroy of the former Kingdom passed to the Governor-General of Warsaw[12]—or, to be more specific, of the Warsaw Military District (Polish: Warszawski Okręg Wojskowy, Russian: Варшавский Военный Округ). However, in the internal correspondence of Russian Imperial offices this functionary was still called namestnik.

The governor-general answered directly to the King and exercised much broader powers than had the namiestnik. In particular, he controlled all the military forces in the region and oversaw the judicial systems (he could impose death sentences without trial). He could also issue "declarations with the force of law," which could alter existing laws.

Notes

a ^ The office is referred to in sources by various names. Namestnik is translated as "viceroy of Poland or f Warsaw. The Governor-General of Warsaw is sometimes referred to as "Governor-General of the Kingdom of Poland" or "Governor-General of Poland." Some sources erroneously apply the term namestnik to the period after 1874, or "governor-general" to the earlier period.

b ^ Sources are contradictory as to whether the namestnik had competence in the military realm. Certainly from 1815 to 1831 the Congress Kingdom's military was controlled by Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich of Russia, who de facto had more power then the namestnik, Józef Zajączek. Zajączek died in 1826 and was not replaced until 1831, when the November 1831 Uprising saw Ivan Paskevich assume the post of namestnik—as well as command of Russian military forces in the region, as he was tasked with defeating the Uprising. The question of who controlled the military after Paskevich's death is unclear, but again the last namestnik, Fyodor Berg, was tasked with crushing another Polish uprising—the January 1863 Uprising—and commanded the military.

Viceroys of the Kingdom of Poland

- Józef Zajączek (1815–26)

- Vacant, 1826–31 (power and responsibilities were exercised by the Administrative Council)

- Ivan Paskevich (1831–55)

- Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov (1855 – 3 May 1861)

- Nikolai Sukhozanet (16 May 1861 – 1 August 1861)

- Karl Lambert (1861)

- Nikolai Sukhozanet (11–22 October 1861)

- Alexander von Lüders (November 1861 – June 1862)

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia (June 1862 – 31 October 1863)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Rembert von Berg (1863–74)

Administrative Council

The Administrative Council (Polish: Rada Administracyjna) was a part of Council of State of the Kingdom. Introduced by the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815, it was composed of 5 ministers, special nominees of the King and the Namestnik of the Kingdom of Poland. The Council executed the King's will and ruled in the cases outside the ministers competence and prepared projects for the Council of State.

The Council was reformed:

- after the death of namestnik Józef Zajączek in 1826

- after the fall of November Uprising in 1831

- after the liquidation of Council of State in 1841

- after the reforms of Aleksander Wielopolski in 1863

- after the fall of January Uprising

It was liquidated on 15 June 1867.

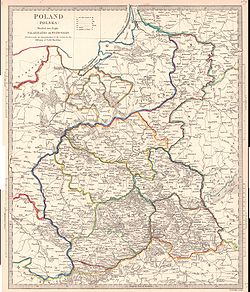

Administrative divisions

The administrative divisions of the Kingdom changed several times over its history. Over the next several decades, various smaller reforms were carried out, either changing the smaller administrative units or merging/splitting various subdivisions.

1815 initial configuration

Immediately after its creation, 1815–1816, the Kingdom of Poland was divided into departments, a relic from the times of the French-dominated Duchy of Warsaw.

1816 Reorganization

On January 16, 1816 the administrative division was reformed from the departments of the Duchy of Warsaw into the more traditionally Polish voivodeships, obwóds and powiats. There were 8 voivodeships:

- Augustów Voivodeship (capital in Suwałki)

- Kalisz Voivodeship

- Kraków Voivodeship (despite the name of this province, the city of Kraków was not included; Kraków was a free city until the Kraków Uprising of 1846; the capital was first Miechów, then Kielce).

- Lublin Voivodeship

- Mazowsze Voivodeship (capital in Warsaw)

- Płock Voivodeship

- Podlasie Voivodeship (capital in Siedlce)

- Sandomierz Voivodeship (capital in Radom)

1837 Reforms

On 7 March 1837, in the aftermath of the November Uprising earlier that decade, the administrative division was reformed once again, bringing Congress Poland closer to the structure of the Russian Empire, with the introduction of guberniyas (governorate, Polish spelling gubernia):

- Augustów Governorate (with capital in Łomża)

- Kalisz Governorate (with capital in Kalisz)

- Kraków Governorate (with capital in Kielce)

- Lublin Governorate (with capital in Lublin)

- Masovia Governorate (with capital in Warsaw)

- Płock Governorate (with capital in Płock)

- Podlasie Governorate (with capital in Siedlce)

- Sandomierz Governorate (with capital in Radom)

1842 Subdivision Renaming

In 1842 powiats were renamed okręgs, and obwóds were renamed powiats.

1844 Reorganization & Consolidation

In 1844 several governorates were merged with others, and some others renamed. 5 governorates remained:

| Governorate | Name in Russian | Name in Polish | Seat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warsaw Governorate | Варшавская губерния | Gubernia warszawska | Warsaw |

| Augustów Governorate | Холмская губерния | Gubernia augustowska | Suwałki |

| Lublin Governorate | Люблинская губерния | Gubernia lubelska | Lublin |

| Płock Governorate | Плоцкская губерния | Gubernia płocka | Płock |

| Radom Governorate | Радомская губерния | Gubernia radomska | Radom |

See also

- Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland

- Grand Duchy of Posen

- History of Poland (1795–1918)

- Grand Duchy of Finland (1809–1917)

- Pale of Settlement

References

- ↑ Nicolson, Harold George (2001). The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. New York: Grove Press. pp. 171. ISBN 0-802-13744-X. http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN080213744X&id=qm5BNjqrGsUC&pg=PA171&lpg=PA171&dq=Congress+Poland+puppet&sig=QeOuv98IrRQBMjDxV-SSShnqHlY.

- ↑ Palmer, Alan Warwick (1997). Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. 7. ISBN 0-871-13665-1. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0871136651&id=d_rlZKhgaekC&pg=PA7&lpg=PA7&dq=Congress+Poland+puppet&sig=mWBTlU5r-93pZ3zW6lCaP3iePE4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century by Agnieszka Barbara Nance, Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin page 169-188

- ↑ Henderson, WO (1964). Castlereagh et l'Europe, w: Le Congrès de Vienne et l'Europe. Paris: Bruxelles. pp. 60.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Miłosz, Czesław (1983). The history of Polish literature. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 196. ISBN 0520044770. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520044770&id=11MVdBYUX5oC&pg=RA1-PA196&lpg=RA1-PA196&dq=congress+constitution+Poland+liberal&sig=vWZzxP8z_z2ELTF98k81ShrdJ3I. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Nicolson, Harold George (2001). The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. New York: Grove Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-802-13744-X. http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN080213744X&id=qm5BNjqrGsUC&pg=PA179&lpg=PA179&dq=congress+Poland+constitution&sig=SR2BlLsFWhYKpKPuj_PRDDMKO44. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ "Kingdom of Poland". The Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia (1890–1906). http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/007/111/111469.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-27. (Russian)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Ludwikowski, Rett R. (1996). Constitution-making in the region of former Soviet dominance. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-822-31802-4. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0822318024&id=qw8o0_c0m74C&pg=RA1-PA12&lpg=RA1-PA12&dq=congress+constitution+Poland+liberal&sig=mtu3Xp979Whlawu_ee2lP75c_QM.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Królestwa Polskiego". Encyklopedia PWN. http://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo.php?id=3925264. Retrieved 2006-01-19. (Polish)

- ↑ Janowski, Maciej; Przekop, Danuta (2004). Polish Liberal Thought Before 1918. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 74. ISBN 9639241180. http://books.google.com/books?visbn=9639241180&id=ieF7NYaEqQYC&pg=PA74&lpg=PA74&ots=LA_l36F5os&dq=Poland+constitution+November+uprising&sig=JBLgctLDj-10Zbg4D4GyLzw-4rc. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ Hugo Stumm, Russia's Advance Eastward, 1874, p. 140, note 1. Google Print [1]

- ↑ Thomas Mitchell, Handbook for Travellers in Russia, Poland, and Finland, 1888, p. 460. Google Print [2]

- Kahan, Arcadius; Weiss, Roger D. (1989). Russian economic history: the nineteenth century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-42243-7.

- Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geographical and Spatial Organization, p. 539, [3]

- (Polish) Mimo wprowadzenia oficjalnej nazwy Kraj Przywiślański terminy Królestwo Polskie, Królestwo Kongresowe lub w skrócie Kongresówka były nadal używane, zarówno w języku potocznym jak i w niektórych publikacjach.

- (English) Despite the official name Kraj Przywiślański terms such as, Kingdom of Poland, Congress Poland, or in short Kongresówka were still in use, both in everyday language and in some publications.

- "Encyklopedia w INTERIA.PL - największa w Polsce encyklopedia internetowa, encyklopedie Biologia, Nauki społeczne, Humanistyka, Historia, Kultura i Sztuka, definicje, słownik synonimów i leksykon.". http://encyklopedia.interia.pl/haslo?hid=96853. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- (Polish) po upadku powstania zlikwidowano ostatnie elementy autonomii Królestwa Pol. (łącznie z nazwą), przekształcając je w "Kraj Przywiślański";

- (English) after the fall of the uprising last elements of autonomy of the Kingdom of Poland (including the name) were abolished, transforming it into the "Privislinsky Krai"

- "Onet.pl Portal wiedzy". Encyclopedia WIEM. http://portalwiedzy.onet.pl/15674,,,,krolestwo_polskie,haslo.html. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- (Polish) "Królestwo Polskie po powstaniu styczniowym: Nazwę Królestwa Polskiego zastąpiła, w urzędowej terminologii, nazwa Kraj Przywiślański."

- (English) "Kingdom of Poland after the January Uprising: the name Kingdom of Poland was replaced, in official documents, by the name of Privislinsky Krai."

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||